My work on: https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~bh/ssch20/io.html

Some of the exercises revisit the Chapter 10 Tic Tac Toe procedure.

Effects and Side Effects, Functions & Procedures

This chapter introduces the idea of effects and side effects. An effect is something like returning a value, computing a value, invoking other procedures, and providing arguments to other procedures. A side effect is something like printing some text to a screen.

Only the last value of a given expression within a procedure gets returned, but lots of side effects (e.g. printing stuff to screen) can occur within a single procedure.

In discussing side effects and introducing the special form begin, the authors note that side effects are not consistent with the idea of functional programming. They draw a distinction between a function, which is something that computes and returns one value, with no side effects, and a procedure, which is a more general concept describing a thing that a lambda returns, and which may or may not be a procedure.

User input – read and read-line

This chapter introduces the idea of user input in the form of various procedures. One is read. It only reads one expression at a time though. It can be a little counter intuitive how it works.

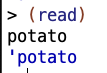

If you invoke (read) and then type one word, what you get is pretty expected:

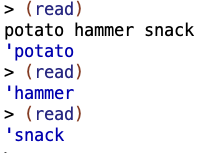

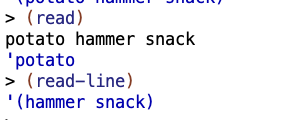

OTOH, if you invoke read and type multiple words….

Note we only got one word back for each invocation of (read), despite the fact that we initially typed three words.

What if you want to input and get back a bunch of words? there’s read-line:

If you mix read and read-line things can get weird

Miscellaneous

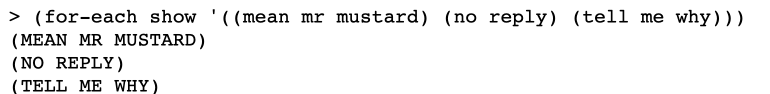

for-each lets you do stuff like invoke show for each element of a list in order:

Exercises

✅ 20.1

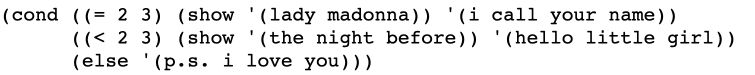

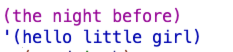

20.1 What happens when we evaluate the following expression? What is printed, and what is the return value? Try to figure it out in your head before you try it on the computer.

I think that ‘(the night before) gets printed and ‘(hello little girl) is the return value, since 2 will always be less than 3.

Correct!

✅ 20.2

What does

newlinereturn in your version of Scheme?

A blank line:

![]()

✅ 20.3

Define

showin terms ofnewlineanddisplay.

My answer:

|

1

2

3

|

(define (myshow input)

(display input) (newline))

|

✅ 20.4

Write a program that carries on a conversation like the following example. What the user types is in boldface.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

> (converse)

Hello, I'm the computer. What's your name? Brian Harvey

Hi, Brian. How are you? I'm fine.

Glad to hear it.

|

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

|

(define (converse)

(display "Hello, I'm am iMac :) What's your name?")

(let ((name (first (read-line))))

(display "Hi, ")

(display name)

(display ". How are you?")

(let ((condition (read-line)))

(cond

((equal? condition '("I'm" good))

(show "Glad to hear it."))

((equal? condition '("I'm" bad))

(show "Sorry :( "))

(else (show "I see.")

)))))

|

I figured out what to check condition as being equal to by invoking read-line, typing the term I wanted to use, and then seeing exactly what got returned:

✅ 20.5

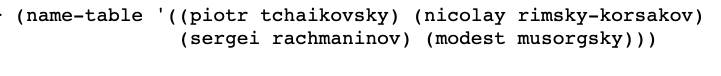

Our

name-tableprocedure uses a fixed width for the column containing the last names of the people in the argument list. Suppose that instead of liking British-invasion music you are into late romantic Russian composers:

Alternatively, perhaps you like jazz:

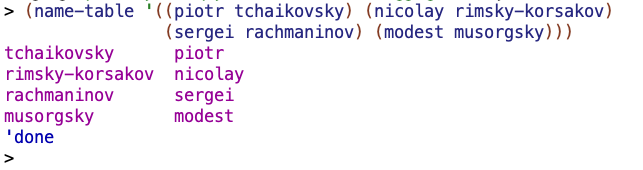

Modifyname-tableso that it figures out the longest last name in its argument list, adds two for spaces, and uses that number as the width of the first column.

I moved the main functionality of name-tables to a helper procedure, name-tables-helper, and used name-tables primarily to call another procedure, longest-last, in order to figure out the proper width and pass it to the helper procedure:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

|

(define (name-table names)

(name-table-helper names (+ 2 (longest-last 0 names))))

(define (name-table-helper names width)

(if (null? names)

'done

(begin (display (align (cadar names) width))

(show (caar names))

(name-table-helper (cdr names) width))))

(define (longest-last countoflongest names)

(cond

((null? names) countoflongest)

((> (count (cadar names)) countoflongest)

(longest-last (count (cadar names)) (cdr names)))

(else (longest-last countoflongest (cdr names)))))

|

Seems to work as intended:

✅ 20.6

20.6 The procedure

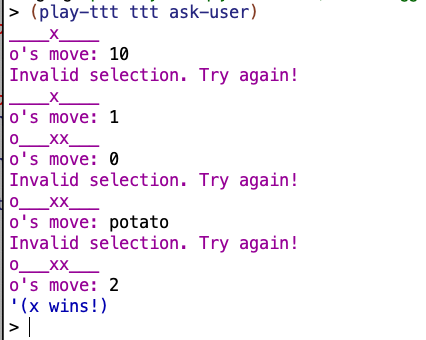

ask-userisn’t robust. What happens if you type something that isn’t a number, or isn’t between 1 and 9? Modify it to check that what the user types is a number between 1 and 9. If not, it should print a message and ask the user to try again.

So the existing ask-user procedure is:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (ask-user position letter)

(print-position position)

(display letter)

(display "'s move: ")

(read))

|

My revised version:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

|

(define (ask-user position letter)

(print-position position)

(display letter)

(display "'s move: ")

(let ((playermove (read)))

(cond

((or (not (number? playermove))

(> playermove 9)

(< playermove 1))

(show "Invalid selection. Try again!")

(ask-user position letter))

(else playermove))))

|

Seems to work:

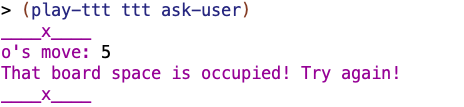

✅ 20.7

Another problem with

ask-useris that it allows a user to request a square that isn’t free. If the user does this, what happens?

you can just overwrite the computer’s moves and the computer will respect the new moves and not overwrite yours, lol. one-sided cheating:

Fix

ask-userto ensure that this can’t happen.

I referred to the detailed mind map I made of the tic tac toe procedure back in Chapter 10 for solving this.

Within the tic tac toe procedure we have substitute-letter, which takes the number of a square (e.g. 5 for the middle square) and the word representing the state of the game board (e.g. ‘____x____ representing the game state “only an x in the middle square, all other spaces free) as arguments. If the square number given is occupied in the game board, substitute-letter returns an ‘x or ‘o as appropriate. If not, it returns a number.

So what we need to do is add a check that playermove returns a number when substitute-letter is called:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

|

(define (ask-user position letter)

(print-position position)

(display letter)

(display "'s move: ")

(let ((playermove (read)))

(cond

((or (not (number? playermove))

(> playermove 9)

(< playermove 1))

(show "Invalid selection. Try again!")

(ask-user position letter))

((not (number? (substitute-letter playermove position)))

(show "That board space is occupied! Try again!")

(ask-user position letter))

(else playermove))))

|

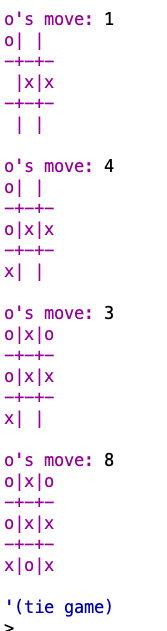

✅ 20.8

At the end of the game, if the computer wins or ties, you never find out which square it chose for its final move. Modify the program to correct this. (Notice that this exercise requires you to make

play-ttt-helpernon-functional.)

I was really confused at first, because I thought by “non-functional” they meant we’d have to break play-ttt-helper somehow, but I think they just mean that it’s no longer a function cuz it has a side effect!

We can fix the deficiency they want by adding a couple of print-position statements to play-ttt-helper:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

|

(define (play-ttt-helper x-strat o-strat position whose-turn)

(cond ((already-won? position (opponent whose-turn))

(print-position position)

(list (opponent whose-turn) 'wins!))

((tie-game? position)

(print-position position)

'(tie game))

(else (let ((square (if (equal? whose-turn 'x)

(x-strat position 'x)

(o-strat position 'o))))

(play-ttt-helper x-strat

o-strat

(add-move square whose-turn position)

(opponent whose-turn))))))

|

I realized I wasn’t using their new Aesthetic Board Display code from Chapter 20, when running tic tac toe examples on my computer, so I added that. Makes things easier to read.

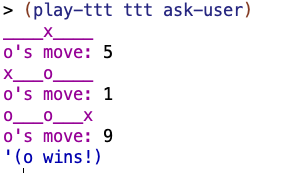

My solution seems to work:

✅ 20.9

The way we invoke the game program isn’t very user-friendly. Write a procedure

gamethat asks you whether you wish to playxoro, then starts a game. (By definition,xplays first.) Then write a proceduregamesthat allows you to keep playing repeatedly. It can ask “do you want to play again?” after each game. (Make sure that the outcome of each game is still reported, and that the user can choose whether to playxorobefore each game.)

My code for game and games:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

|

<br />(define (game)

(show "Do you want to play x or o?")

(let ((choice (read)))

(cond

((equal? choice 'x)

(play-ttt ask-user ttt))

((equal? choice 'o)

(play-ttt ttt ask-user))

(else (show "that's not a valid selection. Try again!")

(game)))))

(define (games)

(game)

(show "Do you want to play again? y/n")

(let ((answer (read)))

(cond

((equal? answer 'y)

(games))

((equal? answer 'n)

(show "Ok. Thanks for playing!")))))

|

It seems to work.