This chapter is about common programming patterns.

The Every Pattern

In the

everypattern, we collect the results of transforming each element of a word or sentence into something else.

One of the things the book talks about is a variation on the letter-pairs procedure. letter-pairs varies from the standard every pattern because it deals with two letters/words at a time:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (letter-pairs wd)

(if (= (count wd) 1)

'()

(se (word (first wd) (first (bf wd)))

(letter-pairs (bf wd)))))

|

The book then suggests tackling the following problem of having non-overlapping pairs (and contrasts the desired functionality with letter-pairs:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

> (disjoint-pairs 'tripoli) ;; the new problem

(TR IP OL I)

> (letter-pairs 'tripoli) ;; compare the old one

(TR RI IP PO OL LI)

|

My first attempt to solve this problem could not handle even-numbered words correctly. This is because I only addressed a base-case where the number of letters remaining was equal to 1 and not where it was empty. If you’re going through a word two letters at a time, you’ve got to be able to handle base cases for both an odd number of letters and an even number of letters. The result of my inadequate procedure was that disjoint-pairs tried to take the first of an empty word when dealing with an input word with an even number of letters:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

(define (disjoint-pairs wd)

(if (= (count wd) 1)

wd

(se (word (first wd) (first (bf wd)))

(disjoint-pairs (bf (bf wd))))))

> (disjoint-pairs 'tripol)

|

![]()

My second attempt failed to properly handle the case where one letter is passed initially, returning a word instead of a sentence (and also didn’t use else):

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

|

(define (disjoint-pairs wd)

(cond ((empty? wd) '())

((= (count wd) 1) wd)

((se (word (first wd) (first (bf wd)))

(disjoint-pairs (bf (bf wd)))))))

(disjoint-pairs 't)

't

|

The working solution fixes the issue with the one-letter input by invoking sentence in the case where there is one letter remaining:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

(define (disjoint-pairs wd)

(cond ((empty? wd) '())

((= (count wd) 1) (se wd))

(else (se (word (first wd) (first (bf wd)))

(disjoint-pairs (bf (bf wd)))))))

|

The Keep Pattern

This time we’ll consider a different kind of problem: choosing some of the elements and forgetting about the others.

Here is an example of a keep-like pattern:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (keep-three-letter-words sent)

(cond ((empty? sent) '())

((= (count (first sent)) 3)

(se (first sent) (keep-three-letter-words (bf sent))))

(else (keep-three-letter-words (bf sent)))))

|

Let’s look at the differences between the

everypattern and thekeeppattern. First of all, thekeepprocedures have three possible outcomes, instead of just two as in mostevery-like procedures. In theeverypattern, we only have to distinguish between the base case and the recursive case. In thekeeppattern, there is still a base case, but there are two recursive cases; we have to decide whether or not to keep the first available element in the return value. When we do keep an element, we keep the element itself, not some function of the element.

Right. A typical every pattern is like this:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (square-sent sent)

(if (empty? sent)

'()

(se (square (first sent))

(square-sent (bf sent)))))

|

Since you’re doing the same thing to each element in a sentence until the sentence is empty, you don’t need to have logic that handles alternatives more complex than “is the sentence empty or not?” But with the keep pattern, you have to both handle the base case and also handle the alternatives of a given element either 1) being kept or 2) not being kept.

As with the

everypattern, there are situations that follow thekeeppattern only approximately. Suppose we want to look for doubled letters within a word:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

> (doubles 'bookkeeper)

OOKKEE

> (doubles 'mississippi)

SSSSPP

|

Here is my solution to this. The (<= (count wd) 1) part lets it handle the empty and one word cases.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (doubles wd)

(cond ((<= (count wd) 1) (word ""))

((equal? (first wd) (first (bf wd)))

(word (first wd) (first (bf wd)) (doubles (bf wd))))

(else (doubles (bf wd)))))

|

I noticed some differences between my solution and their solution (below):

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (doubles wd)

(cond ((= (count wd) 1) "")

((equal? (first wd) (first (bf wd)))

(word (first wd) (first (bf wd)) (doubles (bf (bf wd)))))

(else (doubles (bf wd)))))

|

One difference is that they don’t have (word "") in the first cond line, instead only using "". I think they are right here. word is unnecessary. "" is the empty word, so it’s already a type of word. If you are returning it because you are e.g. calling doubles on a 1-letter word, then since it’s already a word, it doesn’t need to be made into a word by word. This is different than with disjoint-pairs, where we needed to invoke sentence in one of the base cases in order for the program to have the output we wanted. If you are arriving at the empty case after a series of recursive calls to doubles, then doubles will be passed as an argument to word as part of the recursive procedural calls anyways, so passing it to word again in the base case is redundant.

Another difference is that in the recursive call where a match is found, the argument to the recursive invocation of doubles is (bf (bf wd)) instead of (bf wd) as in mine. Again, I think their approach makes sense. English doesn’t have “triples” of the same letter in a word. So, once you have found a match, you can be confident that the two letters that are “doubles” are dealt with for the purposes of the doubles procedure and move onto the next word. However, if you haven’t found a match, you have to continue going character by character (as in (else (doubles (bf wd)))), because you don’t know where the doubled characters will start within a word.

I think my approach is slightly superior in one respect: I handle the case of trying to pass an empty word to doubles whereas the book’s version gives an error message on it.

The Accumulate Pattern

Another pattern is combining all the elements of an argument into a single result:

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

(define (addup nums)

(if (empty? nums)

0

(+ (first nums) (addup (bf nums)))))

|

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

(define (scrunch-words sent)

(if (empty? sent)

""

(word (first sent) (scrunch-words (bf sent)))))

|

Note in both cases the use of the identity element in as the return value in the base case.

If there is no identity element for the combiner, as in the case of

max, we modify the pattern slightly:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (sent-max sent)

(if (= (count sent) 1)

(first sent)

(max (first sent)

(sent-max (bf sent)))))

|

We can go all the way down to the empty sentence and then add 0 to a series of numbers or the empty word to a word and know the result will come out the same. This is because 0 and the empty word are the identity elements for the + and word procedures respectively. If there’s no identity element for the combiner, we want to cut off the recursion before it gets to the empty sentence. With sent-max, we call it quits when the count sent equals 1 and then return the final remaining value in the sentence.

Helper Procedures

Found this section a bit tricky to follow so I’m going to go over it in detail.

Let’s say we want a procedure

every-nththat takes a number n and a sentence as arguments and selects every nth word from the sentence.

|

1

2

3

4

|

> (every-nth 3 '(with a little help from my friends))

(LITTLE MY)

|

We get in trouble if we try to write this in the obvious way, as a sort of

keeppattern.

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

(define (every-nth n sent) ;; wrong!

(cond ((empty? sent) '())

((= n 1) (se (first sent) (every-nth **n** (bf sent))))

(else (every-nth (- n 1) (bf sent)))))

|

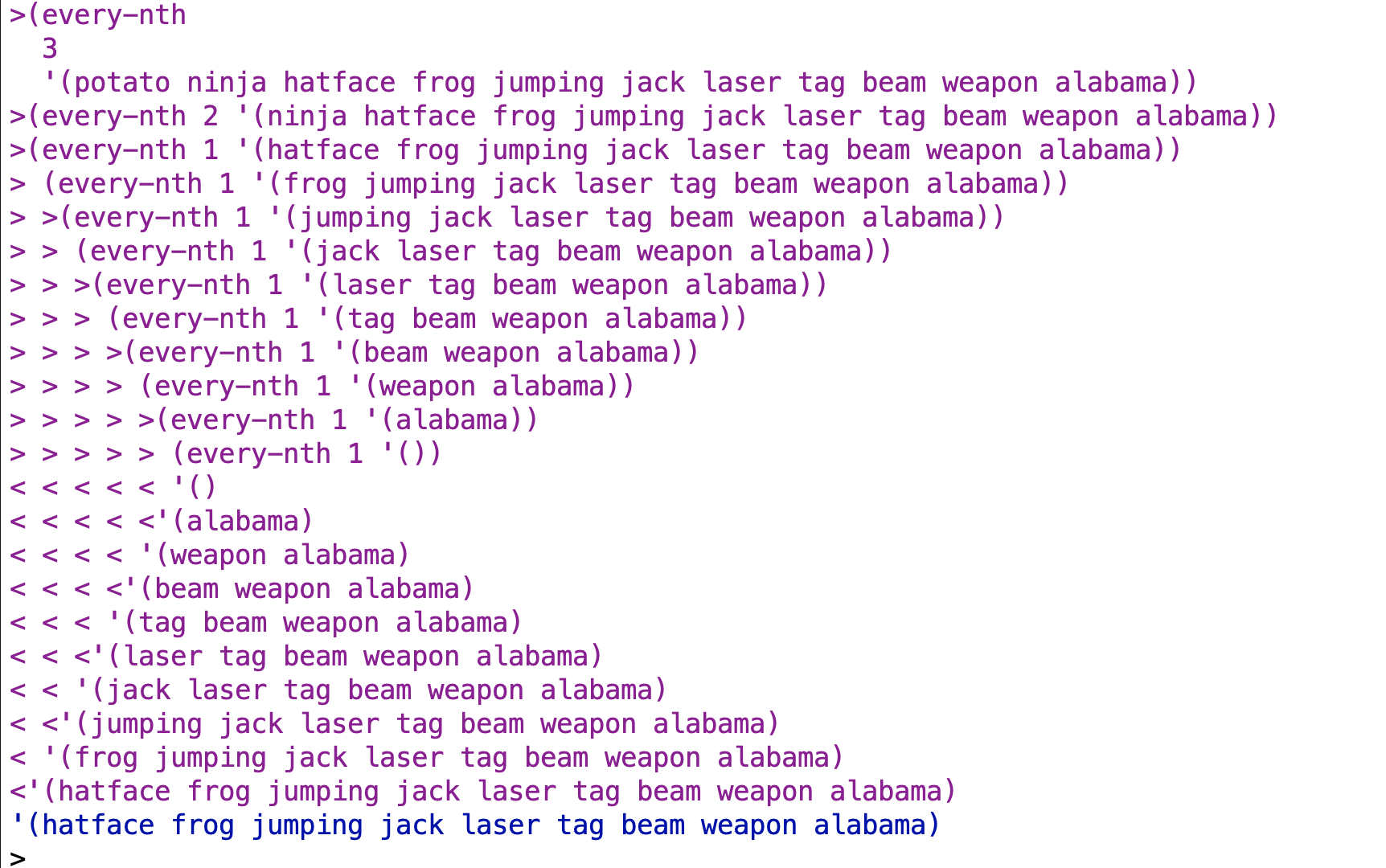

Here’s a trace of this version of the program on some sample input:

The problem is with the

**n**that’s in boldface. We’re thinking that it’s going to be thenof the original invocation ofevery-nth, that is, 3. But in fact, we’ve already countedndown so that in this invocation its value is 1. (Check out the first half of the samecondclause.)

The way the program currently functions is this:

1) if n does not equal 1, the program recursively invokes every-nth with (- n 1) for the n value, up until the point where n does actually equal 1. This “countdown” is what results in the desired interval working one time – e.g. the first two words will be skipped for an n of 3, or the first 3 words will be skipped for an n of 4, and so on.

2) If n does equal 1, then the first value of the sent is returned, and every-nth is invoked with an n of 1. This basically means there is a “countdown” of 1 until the next value from the sentence is returned, leading to every word in the sentence being returned from then on.

3) If the sentence is empty, the empty sentence is returned.

This is not the desired behavior.

This procedure will correctly skip the first two words but will keep all the words after that point. That’s because we’re trying to remember two different numbers: the number we should always skip between kept words, and the number of words we still need to skip this time.

If we’re trying to remember two numbers, we need two names for them. The way to achieve this is to have our official

every-nthprocedure call a helper procedure that takes an extra argument and does the real work:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

(define (every-nth n sent)

(every-nth-helper n n sent))

(define (every-nth-helper interval remaining sent)

(cond ((empty? sent) '())

((= remaining 1) (se (first sent) (every-nth-helper interval interval (bf sent))))

(else (every-nth-helper interval (- remaining 1) (bf sent)))))

|

This version of every-nth takes the same input but provides n twice to a helper procedure, every-nth-helper, which receives the n-values as two arguments, interval (for the interval of words being selected) and remaining (to track the “countdown” to select he next word.)

When remaining is equal to 1, the (first sent) and is combined with a recursive call to every-nth-helper. The key thing here is that interval is provided not only as the first argument to every-nth-helper but as the second argument. The second argument is the the remaining that keeps track of the “countdown” to the next value to be selected from the sentence. By providing interval as the argument for remaining when selecting a sentence, every-nth-helper is “resetting the countdown”.

When remaining is not equal to 1, every-nth-helper just reduces remaining by 1.

This procedure always calls itself recursively with the same value of

interval, but with a different value ofremainingeach time.Remainingkeeps getting smaller by one in each recursive call until it equals 1. On that call, a word is kept for the return value, and we callevery-nth-helperrecursively with the value ofinterval, that is, the original value ofn, as the newremaining. If you like, you can think of this combination of an initialization procedure and a helper procedure as another pattern for your collection.

sent-before?

We want to write the procedure

sent-before?, which takes two sentences as arguments and returns#tif the first comes alphabetically before the second. The general idea is to compare the sentences word by word. If the first words are different, then whichever is alphabetically earlier determines which sentence comes before the other. If the first words are equal, we go on to compare the second words.[5]

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

> (sent-before? '(hold me tight) '(sun king))

#T

> (sent-before? '(lovely rita) '(love you to))

#F

> (sent-before? '(strawberry fields forever) '(strawberry fields usually))

#T

|

Their solution is as follows:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

(define (sent-before? sent1 sent2)

(cond ((empty? sent1) #t)

((empty? sent2) #f)

((before? (first sent1) (first sent2)) #t)

((before? (first sent2) (first sent1)) #f)

(else (sent-before? (bf sent1) (bf sent2)))))

|

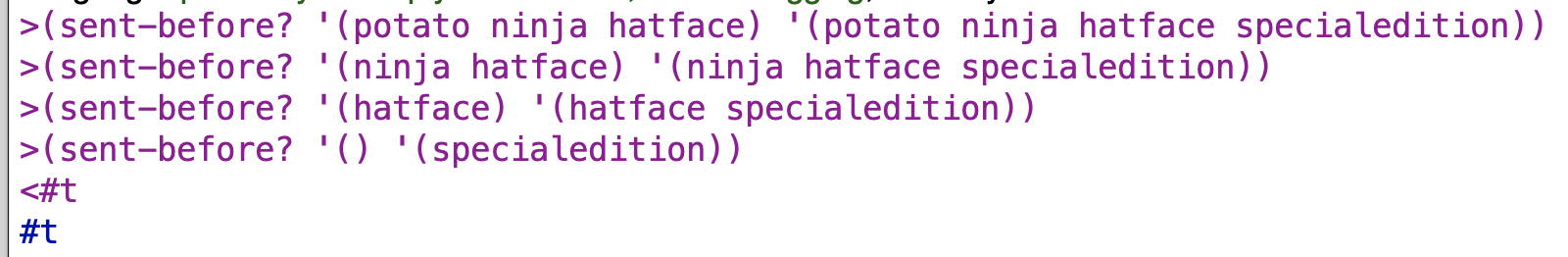

Here’s my explanation of this procedure:

The procedure doesn’t know whether the first or second sentence will have more words, so it needs to be able to handle both cases.

If the first sentence is empty?, that means that the first sentence ran out of words before the second sentence. That could happen if, for example, the first sentence and second sentence had the same 3 words to start, but then the second sentence had another word, e.g.:

|

1

2

|

(sent-before? '(potato ninja hatface) '(potato ninja hatface specialedition))

|

In that case, the first sentence is alphabetically before the second sentence, and so the procedure should return true:

OTOH, if the second sentence runs out of words before the first, that means that the second sentence is alphabetically before the first sentence, so the procedure should return false.

The base case is the only part I thought needed a detailed explanation … the rest seems pretty straightforward to me.

Exercises

Classify each of these problems as a pattern (

every,keep, oraccumulate), if possible, and then write the procedure recursively. In some cases we’ve given an example of invoking the procedure we want you to write, instead of describing it.

✅ Exercise 14.1

|

1

2

3

4

|

> (remove-once 'morning '(good morning good morning))

(GOOD GOOD MORNING)

|

(It’s okay if your solution removes the other

MORNINGinstead, as long as it removes only one of them.)

This seems like a keep to me, though with a twist. We want to keep everything except one instance of the word to remove.

One way to approach this might be to do something like: after you hit the word, you skip over it but just immediately return the rest of the sentence (no recursive call, just a bf sent). Boom, problem solved.

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

(define (remove-once wd-to-remove sent)

(cond ((empty? sent) '())

((equal? wd-to-remove (first sent)) (bf sent))

(else (se (first sent) (remove-once wd-to-remove (bf sent))))))

|

Tests:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

(remove-once 'morning '(good morning good morning))

;(good good morning)

(remove-once 'marning '(good morning good morning))

;'(good morning good morning)

|

✅❌ Exercise 14.2

|

1

2

3

|

(up 'town)

(T TO TOW TOWN)

|

I think this is closest to an every. We’re working our way through the constituent elements of a word and doing something with them. It’s a bit of a twist in that we’re not going letter by letter but instead going through groups of letters.

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

|

(define (up wd)

(if (empty? wd) '()

(se (up (bl wd)) wd)))

|

Correction: Programming solution is correct. Answer re: pattern is wrong. It’s more like accumulate cuz we’re building something up using the recursive call. We’re not transforming each element of something but making a new thing.

✅ Exercise 14.3

|

1

2

3

4

|

(remdup '(ob la di ob la da)) ;; remove duplicates

(OB LA DI DA)

|

(It’s okay if your procedure returns

(DI OB LA DA)instead, as long as it removes all but one instance of each duplicated word.)

This is a keep pattern. We are keeping non-duplicates.

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (remdup sent)

(cond ((empty? sent) '())

((member? (first sent) (bf sent))

(remdup (bf sent)))

(else (se (first sent) (remdup (bf sent))))))

|

If the first word of the sentence is a member of the butfirst of the sentence, then remdup is recursively called with bf sent to skip the duplicate word. Otherwise, sentence is invoked with the first word of the sentence and a recursive call to remdup (bf sent) as arguments, which keeps the first word as part of the result.

✅ Exercise 14.4

|

1

2

3

|

(odds '(i lost my little girl))

(I MY GIRL)

|

This is a keep pattern. We are keeping the odd-numbered words. We aren’t testing the

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

(define (odds sent)

(cond ((= (count sent) 0) '())

((= (count sent) 1) sent)

(else (se (first sent) (odds (bf (bf sent)))))))

|

My test cases and output:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

> (odds '(i lost my little girl))

'(i my girl)

> (odds '(i lost my potato))

'(i my)

|

The ((= (count sent) 1) sent) base case is necessary for handling sentences with odd-numbered numbers of words like '(i lost my little girl). Because the recursive case (else (se (first sent) (odds (bf (bf sent))))))) moves through sent two at a time (with (bf (bf sent))), a sentence with an odd number of words will ultimately have one word remaining. If the recursive call is allowed to run again when the sentence has only 1 word remaining, the program will give an error because bf will be getting called twice on a sentence with only 1 word. Therefore, you need to handle this as a base case.

You also need to handle 0 words left in sent as a base case. This case will come up when the sentence has an even number of words. This is a separate base case because we want to do different things when we have 0 words left versus when we have one word left. When we have 1 word left, that means the word is the last word of a sentence with an odd-numbered number of words, and this being a procedure that returns the odd-numbered words within a sentence, we want to return such a word (which we do by returning sent). When we have 0 words left, that means the sentence had an even number of words, the last of which we may have “skipped past” in our last recursive call to the odds procedure, and so we just want to wrap up the procedure by returning the identity element for se, the empty sentence '().

✅ Exercise 14.5

Write a procedure

letter-countthat takes a sentence as its argument and returns the total number of letters in the sentence:

|

1

2

3

|

> (letter-count '(fixing a hole))

11

|

This is an accumulate pattern. We’re adding up the elements of a sentence into a single thing.

Here’s how i solved this in chapter 8:

|

1

2

3

|

(define (letter-count sent-arg)

(accumulate + (every count sent-arg)))

|

Here’s how I solved it now:

|

1

2

3

4

|

(define (letter-count sent)

(if (empty? sent) 0

(+ (count (first sent)) (letter-count (bf sent)))))

|

I actually wrote a recursive helper procedure first but then I remembered that count exists 🙂

✅ Exercise 14.6

Write

member?.

We’re not taking each element of something and transforming it like with every, and we’re not choosing some elements and forgetting about others like with keep. We’re taking a word and a sentence and reducing them to a single boolean result. It doesn’t quite feel like an accumulate either though. I don’t think it fits within any pattern well.

I wrote member2? to avoid name conflicts with the existing member? procedure.

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

(define (member2? element list)

(cond ((empty? list) #f)

((equal? element (first list)) #t)

(else (member2? element (bf list)))))

|

My tests (making sure that the output is the same as member?):

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

(member? 'a '(a b c d e f))

(member2? 'a '(a b c d e f))

(member? 'a 'apple)

(member2? 'a 'apple)

(member? 'a '(bed apple banana))

(member2? 'a '(bed apple banana))

|

All outputs were as expected.

✅ Exercise 14.7

Write

differences, which takes a sentence of numbers as its argument and returns a sentence containing the differences between adjacent elements. (The length of the returned sentence is one less than that of the argument.)

|

1

2

3

|

> (differences '(4 23 9 87 6 12))

(19 -14 78 -81 6)

|

This seems to be sort of like an every. We’re going through and transforming the elements. We’re not reducing them to 1 single value like in an accumulate. While there is a reduction in the number of values it’s only to (n – 1).

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (differences num-sent)

(if (= (count num-sent) 2)

(- (first (bf num-sent)) (first num-sent))

(se (- (first (bf num-sent)) (first num-sent))

(differences (bf num-sent)))))

|

The base case is when count numsent is equal to 2 because we need two number values to figure out the difference of something. If we set the base case to less than two with this program as written, then we run into the common recursive procedure problem of a procedure trying to take the first of something that is empty.

This program works and generates the appropriate output. It could be further improved by rewriting as a cond in order to handle stuff like one or zero argument cases, but I’m going to skip doing that.

ADDENDUM: AnneB had a different way of solving this:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (differences numbers)

(if (< (count numbers) 2)

‘()

(sentence (- (first (butfirst numbers)) (first numbers))

(differences (butfirst numbers)) )))

|

This method has the base case as the count of numbers being less than 2 and returns '() in that case. This is a bit better than mine, cuz it lets the program handle input sentences with fewer than 2 numbers.

✅ Exercise 14.8

Write

expand, which takes a sentence as its argument. It returns a sentence similar to the argument, except that if a number appears in the argument, then the return value contains that many copies of the following word:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

> (expand '(4 calling birds 3 french hens))

(CALLING CALLING CALLING CALLING BIRDS FRENCH FRENCH FRENCH HENS)

> (expand '(the 7 samurai))

(THE SAMURAI SAMURAI SAMURAI SAMURAI SAMURAI SAMURAI SAMURAI)

|

I’m not sure this strictly falls within the patterns. We’re not keep-ing some elements and disregarding others, we’re not transforming every element, and we’re not accumulating things into a single value.

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

|

(define (expand-helper num wd)

(if (= num 0) '()

(se wd (expand-helper (- num 1) wd))))

(define (expand sent)

(cond ((empty? sent) '())

((number? (first sent))

(se (expand-helper (first sent) (first (bf sent))) (expand (bf (bf sent)))))

(else (se (first sent) (expand (bf sent))))))

|

The structure of the expand procedure is as follows: first it checks if the sentence is empty and returns the empty sentence if so. Then it checks if the first word in the sentence is a number. If so, it passes both that number and the word that follows it to a helper procedure expand-helper. An invocation of sentence joins the result of expand-helper and a recursive call to expand. The recursive call to expand is made with a sent that has been reduced by two words due to the use of two butfirsts. If the sentence is not empty and the first word of it is not a number, then sentence is invoked with the first word of sent and a recursive invocation of expand used as arguments. This recursive invocation of expand only moves ahead one word in the sentence.

✅ Exercise 14.9

Write a procedure called

locationthat takes two arguments, a word and a sentence. It should return a number indicating where in the sentence that word can be found. If the word isn’t in the sentence, return#f. If the word appears more than once, return the location of the first appearance.

|

1

2

3

4

|

> (location 'me '(you never give me your money))

4

|

This is a procedure where we’re going through and searching for whether one value matches another and then returning the location. I don’t think this fits neatly into any of the patterns. ADDENDUM: AnneB argues this is a keep pattern “except we are not keeping an element of the input sentence, but instead keeping the location of that element. We are also stopping once we find one position to keep, and not looking at the rest of the sentence.” I don’t strongly disagree but I’m not sure I’m convinced either. Those two differences sound pretty major to me.

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

(define (location wd sent)

(cond ((not (member? wd sent)) #f)

((equal? wd (first sent)) 1)

(else (+ 1 (location wd (bf sent))))))

|

Additional test:

|

1

2

3

4

|

> (location 'me '(potato hammer))

#f

|

✅ Exercise 14.10

Write the procedure

count-adjacent-duplicatesthat takes a sentence as an argument and returns the number of words in the sentence that are immediately followed by the same word:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

> (count-adjacent-duplicates '(y a b b a d a b b a d o o))

3

> (count-adjacent-duplicates '(yeah yeah yeah))

2

|

This seems sort like a mix of keep and accumulate. Not all the words are used — only the words that meet certain criteria get counted (kinda like keep). Words followed by a duplicate return a 1, otherwise they return a 0. The 1’s get added up (getting reduced to a single value, kinda like with accumulate).

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

(define (is-dupe wd1 wd2)

(if (equal? wd1 wd2) 1 0))

(define (count-adjacent-duplicates sent)

(if (= (count sent) 1) 0

(+ (is-dupe (first sent) (first (bf sent))) (count-adjacent-duplicates (bf sent)))))

|

The base case tests for one word remaining to avoid the issue of calling butfirst on an empty sentence. At the point there is only one word left in the sentence, we know there will be no more duplicates.

Each pair of values within the sentence is tested for being a duplicate with the helper procedure is-dupe. If they are a duplicate, this helper returns 1, and if not, it returns 0. The values are summed by +.

I should have named is-dupe something like check-if-dupe.

✅ Exercise 14.11

Write the procedure

remove-adjacent-duplicatesthat takes a sentence as argument and returns the same sentence but with any word that’s immediately followed by the same word removed:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

> (remove-adjacent-duplicates '(y a b b a d a b b a d o o))

(Y A B A D A B A D O)

> (remove-adjacent-duplicates '(yeah yeah yeah))

(YEAH)

|

Conceptually this is a keep procedure in that we’re going through some elements and only keeping those that meet a certain criteria (i.e. not being a duplicate).

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

(define (is-dupe wd1 wd2)

(if (equal? wd1 wd2) '() wd1))

(define (remove-adjacent-duplicates sent)

(if (<= (count sent) 1) sent

(se (is-dupe (first sent) (first (bf sent))) (remove-adjacent-duplicates (bf sent)))))

|

I followed the style of my previous answer but with some modifications.

If the count of the sentence gets down to 1, we want to return sent, since that’s the last word of the sentence. Our instruction is to remove any word that is immediately followed by the same word. The last word of the sentence will, by definition, never be followed by the same word, or any other word for that matter.

If the count isn’t 1, we call our modified helper procedure with the first two words in the sentence. The helper procedure returns the empty sentence if the words match, which effectively removes the first word from the sentence. If the words don’t match, it returns wd1, which keeps the first word within the sentence. We don’t need to really worry about wd2 right now except insofar as we are using it for comparison. (If, in the next recursive procedure call, there are still at least two words left, then our current wd2 will be wd1 then.) Using sentence, we combine the results of is-dupe and a recursive call to remove-adjacent-duplicates.

Again, I should have named is-dupe something like check-if-dupe.

ADDENDUM: Initially I had the base case of remove-adjacent-duplicates as (if (= (count sent) 1) sent, but I ultimately rewrote it as you see above. The rewrite handles an empty sentence as input.

✅ Exercise 14.12

Write a procedure

progressive-squares?that takes a sentence of numbers as its argument. It should return#tif each number (other than the first) is the square of the number before it:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

> (progressive-squares? '(3 9 81 6561))

#T

> (progressive-squares? '(25 36 49 64))

#F

|

I don’t think this fits neatly into keep, every, or accumulate.

ADDENDUM: AnneB argues that this is an accumulate pattern because the procedure accumulates using and. I disagree because the elements of the input sentence themselves are not being combined into a single result. Instead, if they pass the test of being a square, they get changed into a truth value, and those truth values are arguably accumulated. But transforming + accumulating is at least a somewhat different kind of thing than just accumulating.

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

|

(define (square num)

(* num num))

(define (is-square? num1 num2)

(if (equal? (square num1) num2) #t #f))

(define (progressive-squares? sent)

(if (<= (count sent) 1) #t

(and (is-square? (first sent) (first (bf sent))) (progressive-squares? (bf sent)))))

|

This is pretty similar to some of my last few solutions. Here I’m using and as the thing combining values, and I’m dealing with true/false values instead of words or numbers.

ADDENDUM: Initially I had the base case of remove-adjacent-duplicates as (if (<= (count sent) 1) #t, but ultimately rewrote it as you see above. The rewrite handles an empty sentence as input.

✅ Exercise 14.13

What does the

piglprocedure from Chapter 11 do if you invoke it with a word like “frzzmlpt” that has no vowels? Fix it so that it returns “frzzmlptay.”

They use pigl as an every example in the text.

Here is the original pigl procedure:

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

(define (pigl wd)

(if (member? (first wd) 'aeiou)

(word wd 'ay)

(pigl (word (bf wd) (first wd)))))

|

with a vowel-less word, the pigl procedure recursively calls itself endlessly, trying to find a vowel.

I incorporated a vowel? procedure. My solution seems maybe a bit inelegant but it does the job:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

|

(define (vowel? letter)

(member? letter 'aeiou))

(define (contains-vowel? wd)

(cond ((member? 'a wd) #t)

((member? 'e wd) #t)

((member? 'i wd) #t)

((member? 'o wd) #t)

((member? 'u wd) #t)

(else #f)))

(define (pigl wd)

(if (not (contains-vowel? wd)) (word wd 'ay)

(if (vowel? first wd))

(word wd 'ay)

(pigl (word (bf wd) (first wd))))))

|

ADDENDUM: I realized I only needed one if statement:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

(define (pigl wd)

(if (or

(not (contains-vowel? wd))

(vowel? (first wd)))

(word wd 'ay)

(pigl (word (bf wd) (first wd)))))

|

ADDENDUM: I thought he difference in the way AnneB and I handled this was interesting. I basically made a special check for the no-vowel case using a helper procedure, while AnneB made a helper that did a countdown based on the length of the word to ensure that each letter was only checked once.

ADDENDUM: I had some intuition that my helper procedure was inelegant. I found a better one from pongsh

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

(define (has-vowel? wd)

(cond ((empty? wd) #F)

((member? (first wd) 'aeiou) #T)

(else (has-vowel? (bf wd)))))

|

Instead of checking the input word for the presence of each vowel, it checks each letter of the word against a word with all the vowels.

✅ Exercise 14.14

Write a predicate

same-shape?that takes two sentences as arguments. It should return#tif two conditions are met: The two sentences must have the same number of words, and each word of the first sentence must have the same number of letters as the word in the corresponding position in the second sentence.

non-standard pattern. AnneB says it’s an accumulate. Same disagreement as in 14.12 so see that for my explanation of my current view.

|

1

2

3

4

|

> (same-shape? '(the fool on the hill) '(you like me too much))#T

> (same-shape? '(the fool on the hill) '(and your bird can sing))#F

|

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

(define (same-shape? sent1 sent2)

(cond ((and (empty? sent1) (empty? sent2)) #t)

((or (empty? sent1) (empty? sent2)) #f)

((not (equal? (count (first sent1)) (count (first sent2)))) #f)

(else (same-shape? (bf sent1) (bf sent2)))))

|

Explanation:

![]()

If both sentences are empty, return true, because this will mean that the sentences were the same “shape”.

![]()

If either sentence is empty (but not both, since we already tested for that) then return false, since that means that one sentence ran out of words before the other sentence, failing one of our conditions.

![]()

If it is not the case that the first word of sent1 and sent2 have the same number of characters, return false. This ensures that the number of letters of each word in the respective sentences are the same when the program returns true.

![]()

We arrive at the else only if neither sentence is empty and if the first words of the respective sentences are the same length. In that case, we recursively call same-shape? with the butfirsts of both sentences.

This procedure is a bit inefficient cuz it tests the length of the sentences each time when you really only need to do that once. If you cared about efficiency, you could do the length test once and do the rest of the stuff in a helper. I’m not worried about the performance of this program on my Mac though 🙂

✅ Exercise 14.15

Write

merge, a procedure that takes two sentences of numbers as arguments. Each sentence must consist of numbers in increasing order.Mergeshould return a single sentence containing all of the numbers, in order. (We’ll use this in the next chapter as part of a sorting algorithm.)

|

1

2

3

|

> (merge '(4 7 18 40 99) '(3 6 9 12 24 36 50))

(3 4 6 7 9 12 18 24 36 40 50 99)

|

Initially was not sure re: pattern. It’s not straightforward. I think every is the closest.

It’s definitely not a keep because we’re not discarding anything, so that one is is easy.

It’s not a straightforward accumulate cuz we’re not reducing the elements of an argument to a single result. We are, however, taking two sentence arguments and reducing them to a single sentence.

Maybe every is the closest. We’re not collecting the results of transforming each element of a sentence into something else. We are, however, collecting the results of reordering the elements of two sentences.

My answer:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

(define (smaller-num-first? num1 num2)

(if (< num1 num2) #t #f))

(define (merge sent1 sent2)

(cond ((and (empty? sent1) (empty? sent2)) '())

((empty? sent1) sent2)

((empty? sent2) sent1)

((smaller-num-first? (first sent1) (first sent2))

(se (first sent1) (merge (bf sent1) sent2)))

(else (se (first sent2) (merge sent1 (bf sent2))))))

|

Without ((empty? sent2) sent1), this happens with their example input:

That’s because the second sentence runs out of numbers first, since the first sentence is the one with the highest number. If you give the second sentence the highest number, then you need ((empty? sent1) sent2) or else the procedure breaks in the same way.

Since this sort of procedure wouldn’t normally wind up with both sentences empty, I think ((and (empty? sent1) (empty? sent2)) '()) only handles the case where you provide two empty sentences as arguments.

smaller-num-first? tests whether the first number from the first sentence is smaller than the first number of the second sentence. If that’s true, I invoke sentence with the first number of the first sentence as the first argument, since it is the smaller number and we want these sorted in order. I then recursively call merge with (bf sent1) and sent2. We only want to bf the first sentence since it’s only a number from the first sentence that we’ve sorted so far.

If none of these other conditions are met, I assume the second number is the smaller of the two numbers and recursively call merge accordingly.

ADDENDUM: Not sure why I broke out the test for whether the smaller number was first was in a helper procedure, as it is quite easy to check directly as AnneB does:

|

1

2

|

((< (first list1) (first list2))

|

✅ Exercise 14.16

Write a procedure

syllablesthat takes a word as its argument and returns the number of syllables in the word, counted according to the following rule: the number of syllables is the number of vowels, except that a group of consecutive vowels counts as one. For example, in the word “soaring,” the group “oa” represents one syllable and the vowel “i” represents a second one.

Be sure to choose test cases that expose likely failures of your procedure. For example, what if the word ends with a vowel? What if it ends with two vowels in a row? What if it has more than two consecutive vowels?

(Of course this rule isn’t good enough. It doesn’t deal with things like silent “e”s that don’t create a syllable (“like”), consecutive vowels that don’t form a diphthong (“cooperate”), letters like “y” that are vowels only sometimes, etc. If you get bored, see whether you can teach the program to recognize some of these special cases.)

non-standard pattern.

First Attempt

Here’s my first attempt at an answer for the basic part of this question. It only handles vowel groupings that are two letters long and does not address any of the special cases:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

|

(define (vowel? letter)

(member? letter 'aeiouAEIOU))

(define (syllables wd)

(cond ((empty? wd) 0)

((and

(> (count wd) 1)

(vowel? (first wd))

(vowel? (first (bf wd))))

(+ 1 (syllables (bf (bf wd)))))

((vowel? (first wd)) (+ 1 (syllables (bf wd))))

(else (+ (syllables (bf wd))))))

|

I think it’s relatively straightforward with one exception. In the line that handles two vowels next to each other, ((and (> (count wd) 1)(vowel? (first wd))(vowel? (first (bf wd)))) (+ 1 (syllables (bf (bf wd))))), I have (> (count wd) 1). That’s there so that the rest of that line does not run in the situation where there is a vowel and only one letter remaining, like when a word ends in a vowel – as with “bake” – or consists of a single vowel.

Had some trouble figuring out an improved solution that would handle multiple vowels next to each other.

Second Attempt

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

(define (vowel-segment wd)

(cond ((empty? wd) "")

((consonant? (first wd)) "")

((vowel? (first wd)) (word (first wd) (vowel-segment (bf wd))))

(else (vowel-segment (bf wd)))))

(define (syllables wd)

(cond ((empty? wd) 0)

((vowel? (first wd)) (+ 1 (syllables ((repeated bf (count (vowel-segment wd))) wd))))

(else (syllables (bf wd)))))

|

This procedure does the job but i’m afraid it’s “cheating” a bit because it’s using the higher order procedure repeated and i think maybe we’re not supposed to use those for recursive exercises.

The basic idea here is that I’m using syllables to find out when a vowel starts and then using vowel-segment to figure out the actual content of the grouping of vowels. I can then use count to figure out how big the group of vowels is and repeated bf [number of vowels] to skip over however many vowels in a row there are.

Third Attempt

I coded around the “higher order procedure” issue by just making a special case recursive bf-repeater procedure, lol:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

|

(define (vowel? letter)

(member? letter 'aeiouAEIOU))

(define (consonant? letter)

(not (vowel? letter)))

(define (bf-repeater wd num)

(if (= num 0) wd

(word (bf-repeater (bf wd) (- num 1)))))

(define (vowel-segment wd)

(cond ((empty? wd) "")

((consonant? (first wd)) "")

((vowel? (first wd)) (word (first wd) (vowel-segment (bf wd))))

(else (vowel-segment (bf wd)))))

(define (syllables wd)

(cond ((empty? wd) 0)

((vowel? (first wd)) (+ 1 (syllables (bf-repeater wd (count (vowel-segment wd))))))

(else (syllables (bf wd)))))

|

Fourth Attempt (Final Answer)

Wasn’t happy with last approach, so I tried another approach: looking for boundaries between vowel and consonant. This approach has the advantage of only needing to consider two letters at a time – rather than needing to keep track of a whole group of vowels†, you only need to check whether two letters represent a boundary between vowels and consonants. And if a vowel ends the sentence you can treat that as a special case.

†You typically don’t need to worry about three letter vowel groups in English but the authors raised the issue as part of the exercise so I wanted to make sure my procedure could handle it.

After some iterating I came up with this:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

|

(define (vowel? letter)

(member? letter 'aeiouAEIOU))

(define (consonant? letter)

(not (vowel? letter)))

(define (vowel-consonant-boundary wd)

(if (and (vowel? (first wd))(consonant? (first (bf wd))))

1 0))

(define (silent-e wd)

(if (member? wd '(ace age ape bake like cooperate one)) -1 0))

(define (no-dipthong wd)

(if (member? wd '(naive continnuum cooperate boa)) 1 0))

(define (syllables-helper wd)

(cond ((empty? wd) 0)

((and (= (count wd) 1)(vowel? wd)) 1)

((vowel? (first wd)) (+ (vowel-consonant-boundary wd) (syllables-helper (bf wd))))

(else (syllables-helper (bf wd)))))

(define (syllables wd)

(+ (silent-e wd) (no-dipthong wd) (syllables-helper wd)))

|

Some explanation:

vowel-consonant-boundary looks for when a vowel follows a consonant and returns 1 if that’s the case and 0 if not. So with a word like apple, the letter group ap gets counted as one syllable, as does the letter group le. Or with soaring, the ar gets counting as a syllable, as does the in. It’s the transition points between vowel and consonant that seem to demarcate a syllable, so those seem like the logical thing to count.

((and (= (count wd) 1)(vowel? wd)) 1) returns 1 if the last letter is a vowel. This handles cases where there are single letter or short words ending in a vowel. For example, “a” is a word with no vowels that precede consonants cuz it only has 1 letter. “boo” likewise has no vowels preceding consonants. ((and (= (count wd) 1)(vowel? wd)) 1) ensures that these words get at least one syllable.

For the special cases like silent-e, I wasn’t aware of some overall pattern in the word that I could search for, so I conceptualized the solution as basically having a list of words that have a silent-e. I only picked a few examples – I’m sure I could have found a huge list and pasted them in, but I didn’t see the point in that. My goal was to figure out how to solve the overall programming problem assuming that I’d use a word list for handling special cases, not fully address the special cases. So the word lists I used are short and only illustrative.

For silent-e words we want 1 syllable less than default behavior (“like” would give two syllables under our standard rule but we only want 1).

For words like “continuum” that have adjacent vowels without a dipthong (meaning “u” and “um” are two different sounds – you don’t say con-tin-um, you say con-tin-you-um) we want one more syllable than the default behavior.

The book used the example of “cooperate” for no-dipthong, but that’s a tricky one to bring up cuz it actually has both a no-dipthong adjacent vowel thing (co-op) and a “silent e” at the end (you don’t say co-op-er-ayt-ee, you say co-op-er-ayt – the e has some affect in terms of what sound the “a” makes but it’s not its own sound). But with this organization of the program “cooperate” can be in both lists and get counted accordingly – the +1 and -1 offset.

tests:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

|

(syllables 'soaring)

2

(syllables 'a)

1

(syllables 'apple)

2

(syllables 'like)

1

(syllables 'blaaarghaae)

2

(syllables 'cooperate)

4

(syllables 'continnuum)

4

(syllables 'bee)

1

(syllables 'america)

4

(syllables 'boa)

2

(syllables 'one)

1

(syllables 'boo)

1

|

Other Solutions

I’m going to try analyzing other solutions to this problem like AnneB did. I think it’s a good idea.

buntine

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

(define (count-syllables wd n repeats)

(let ((increment (if (> repeats 0) 1 0)))

(cond

((empty? wd) (+ increment n))

((vowel? (first wd))

(count-syllables (bf wd) n (+ repeats 1)))

(else

(count-syllables (bf wd) (+ increment n) 0)))))

(define (syllables wd)

(count-syllables wd 0 0))

|

repeats represents consecutive vowels.

n represents the total syllable count.

|

1

2

|

(let ((increment (if (> repeats 0) 1 0)))

|

Set increment to 1 if repeats is greater than 0, or to 0 otherwise. (in other words, if there was a preceding vowel, set increment to 1)

|

1

2

3

|

(cond

((empty? wd) (+ increment n))

|

If the word is empty, add increment and n. This is the value that will return at the end of the procedure.

|

1

2

3

|

((vowel? (first wd))

(count-syllables (bf wd) n (+ repeats 1)))

|

If the first letter is a vowel, recursively call count-syllables with bf of wd, the same n, and (+ repeats 1) for repeats. This will have the result of setting increment to 1 in the recursive call.

|

1

2

3

|

(else

(count-syllables (bf wd) (+ increment n) 0)))))

|

Otherwise (meaning, if the first letter of wd is a consonant), recursively call count-syllables with bf wd, add increment and word and pass that in as n, and pass in 0 for repeat.

So how does this program function in the big picture?

Every time this procedure hits a vowel, the next recursive call to the function will have increment set to 1. The next time the program hits a non-vowel, or the end of the program, the increment and n values get summed, and this is the value that gets returned when the program finishes (when the word is empty). So what the program is basically tracking as a syllable is the sum of the number of transitions from vowels to consonants, with an additional syllable added on if the word ended in a vowel or vowels.