Introduction

People often find criticism from others painful. This is particularly true when the criticism involves a negative moral judgment. Why?

For example, suppose that Mary complains about her life situation to her friend John. Suppose Mary is having money and job trouble. Suppose also that she leads what many would consider to be an irresponsible lifestyle. She spends lots of time at parties and socializing and drinking. Her partying lifestyle means she is often tired, late for work, and not a diligent employee. She lives beyond her means, is always behind on her bills and juggling credit cards, and is not taking steps to improve the situation she is complaining about.

Suppose that John tells Mary he thinks that Mary is responsible for her life and is refusing to take responsibility for it. He argues that there is a connection between Mary’s lifestyle, which he views as irresponsible, and the problems Mary is complaining about. Mary takes this very badly and feels hurt by it. Why?

Considering an Alternative Reaction: Confidence

To understand the answer, it can be helpful to consider an alternative reaction to taking criticism badly – namely, taking criticism well. There are lots of potential criticisms people could offer us that would not cause us to feel hurt. Why?

One important case is when we think the person offering a criticism is wrong and are confident in our position. In that case, the other person’s criticism doesn’t hurt. We may think they are mistaken or misguided or perhaps even a fool, but their criticism doesn’t bother us.

For example, if someone is very confident in their reasons for living life as a teetotaler (someone who doesn’t drink alcohol), then other people’s criticisms and even negative judgments won’t affect the teetotaler. People might say all sorts of things, such as “You’re no fun” or “I don’t trust people who don’t drink” and the teetotaler won’t care. They won’t care because they have some reasons for their behavior which they believe in and which can stand up to conventional views and arguments.

Thinking Someone Has a Point

So Mary, who was criticized by John for her irresponsible lifestyle in the example I mentioned earlier, must not be confident in her judgment regarding her lifestyle. Why?

Maybe, at some level, Mary thinks John has a point. She may not fully agree with his perspective, but she can’t fully rebut it either. So she at the very least has some doubts and is worried John may be right.

This is only a partial explanation. We can think someone has a point about something and not have it bother us. Lots of intellectual or political discussions involve two people who think maybe the other guy has some worthwhile arguments but is overall wrong, and lots of people enjoy having those kinds of discussions and aren’t hurt by them. So there is something else going on with Mary’s situation that causes her to feel hurt.

Lack of Confidence & Second-handedness

Maybe Mary lacks confidence about her views on things in general. She doesn’t really have her own strong opinions about stuff. She kind of just goes with the flow and with what other people are saying. She lives her life trying to get good vibes from others. She interprets John as giving her bad vibes, which she doesn’t like.

So maybe Mary is second-handed, emotionally-oriented and not very intellectual. Maybe she reacted to John from that kind of perspective. That is a bad way to be. It’s important to have considered views on things and to be able to argue for why you do things, for why you lead your life in a certain way. There is that old cliché about a parent asking you if you’d jump off a bridge if all your friends were doing it. Most people recognize that answering “Yes” to such a question is dumb, but the guiding principle of their life is often to answer “Yes” and follow the herd in many cases.

Morality as Scarecrow

Mary may have reacted badly because she felt apprehension at John’s moral judgment. People often treat morality as the thing which constrains their liberty and denies them fun. As Rand puts it in Galt’s speech in Atlas Shrugged:

Morality, to you, is a phantom scarecrow made of duty, of boredom, of punishment, of pain, a cross-breed between the first schoolteacher of your past and the tax collector of your present, a scarecrow standing in a barren field, waving a stick to chase away your pleasures—and pleasure, to you, is a liquor-soggy brain, a mindless slut, the stupor of a moron who stakes his cash on some animal’s race, since pleasure cannot be moral.

Mary likes some aspects of her current lifestyle. She is having some problems, too, though, but she wants to keep her current lifestyle. John offered some criticisms which Mary felt threatened by. She felt threatened because the arguments drew a connection between the lifestyle Mary wants to keep and the problems Mary dislikes. She took John’s criticisms as “a scarecrow standing in a barren field, waving a stick to chase away [her] pleasures.” Moral arguments like John’s are a threat which threaten to take away the stuff she likes and control her life in ways she disagrees with. She hasn’t taken seriously the possibility that morality could actually improve her life in a way she would be okay with.

Misunderstanding Criticism

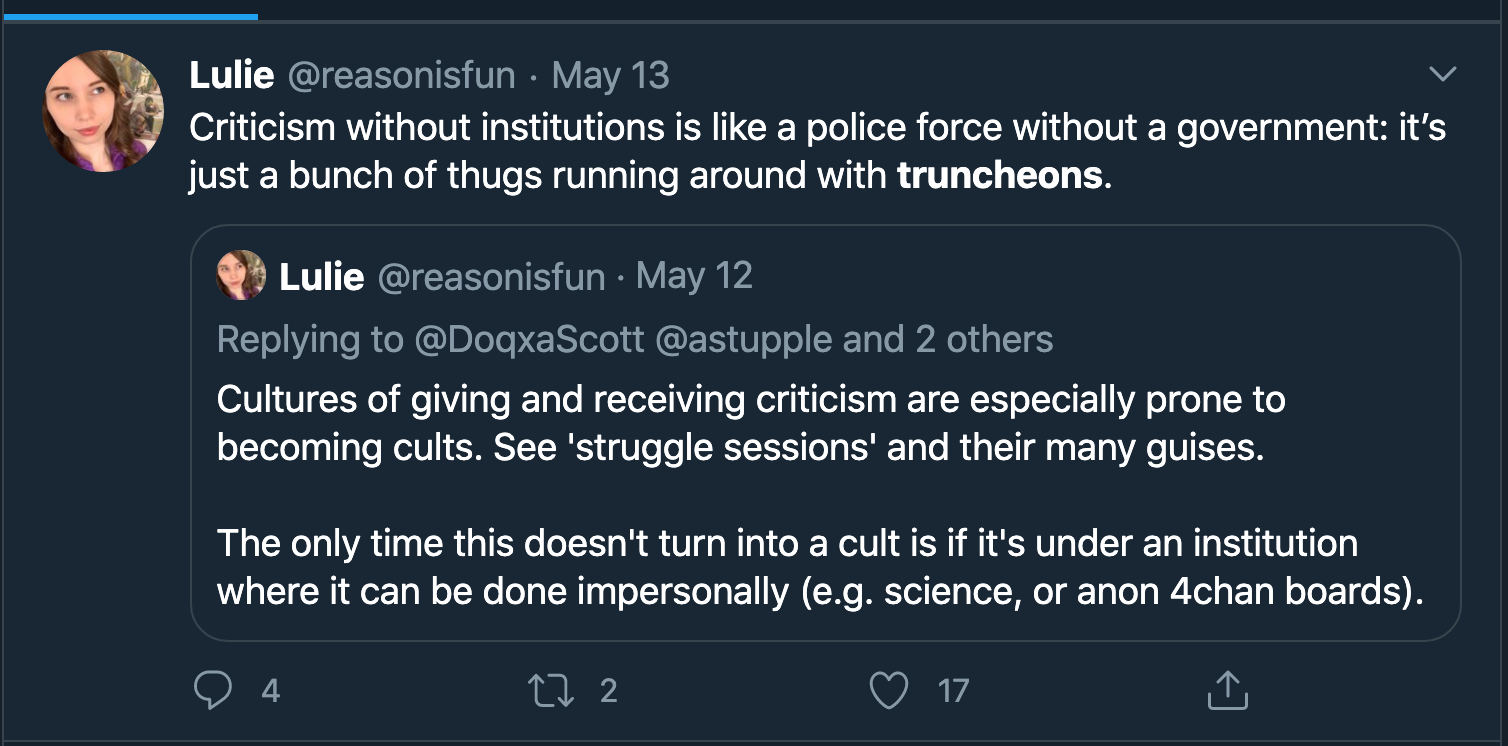

Some people experience criticism as inherently painful, and compare it to things like (being hit with) a truncheon:

Just to be clear, this is a criticism (of pacifism, by Ayn Rand):

This is a truncheon:

So maybe Mary has the (very common) attitude that mixes these things up.

Someone offering an argument that you are making some mistake is obviously pretty different than them hitting you with a stick. If they seem similar to you, you have mistaken ideas about the world. (It’s a similar issue to how people mix up dollars and guns, which is an issue Rand talks about.)

There is a complicating factor here, though. Often people do say things that seem like criticism as part of some power play or social game or just to be mean. People may think that insults sound harsh, and they think that arguments that they are living their life in a bad way also sound harsh. They then group those under the same category of “criticism”, which they associate with harshness and meanness.

If people just say some insult to be mean, that’s not even really a criticism, since it doesn’t try to explain something you are wrong about. If someone just calls you a loser or an idiot, that’s not really a criticism. There’s no argument there, no suggestion for things you can change. You can just ignore that stuff. That’s not what John was doing and not what Mary is bothered about, though.

If someone offers an argument that you are doing something wrong and you can’t easily rebut it, you should take it seriously. That’s what criticism allows us to do – make corrections and learn from other people instead of banging our head into the wall endlessly making the same mistakes. Criticism is not a truncheon but a gift that lets us lead a better life.

Sometimes people will mix nastiness with some genuine point/criticism/argument. Often if someone wants to hurt someone else, it is helpful for that goal to combine meanness and insults with some truth. That can be hard to deal with. Even in that case, though, you should try to separate out the criticism from the nastiness and deal with the criticism intellectually. Even if John had said his points in an aggressive and mean way, Mary should still try to separate out the criticism from the meanness and deal with it intellectually.

One reason to have this policy is you shouldn’t disregard what might be a good point just because it was delivered nastily. This is a bit like not judging a book by its cover.

Another reason to have such a policy is that misunderstandings about the intent and motives of other people in offering criticism are common. For example, people often interpret others as being mean when they are just a bit more blunt than is typical. Another issue is that people will think that if a problem was bad enough for another person to bring up, then the other person must think the problem is really bad, since most people avoid bringing up problems. But some people just have less of a filter than others on what they say. Because of differences in temperament and communication style, it is important not to throw out the criticism baby with the style-it-was-delivered-in bathwater because you (possibly wrongly) attribute a bad motive or intent to the person offering you the criticism.

Not Seeing a Way to Move Forward on the Criticism

It’s common that people are frustrated by criticism because they don’t see a way to act on it or move forward in their situation. For example, Mary might think that her natural temperament is just that of a party girl, that that is her essential nature and what makes her happy, and so John pointing out the problems resulting from such a lifestyle is just him pointing out stuff that she can’t change.

If Mary said those things, John might argue back that lots of people change their habits and activities in ways they wind up liking. He might say that she doesn’t have to give up the stuff she likes entirely to solve her immediate problem, but just moderate her spending some and do a bit less partying and be a bit more diligent at work. Maybe she could try that and see if she likes it?

Mary might shut down the discussion before John can ever get to the point of offering his arguments, though, by assuming John is offering his criticism in a bad faith attempt to hurt her. That is a way many discussions end. Presuming good faith and trying to get value even out of criticism offered in bad faith (like I talked about in the last section) can help. Another thing that can help is trying to be less emotionally reactive in general.

Taking Sides in a Disagreement With Part of Yourself

Another thing that may cause Mary to feel hurt is that she agrees with John and sees some problems with her lifestyle. Maybe she’s been through cycles of engaging in her irresponsible lifestyle and feeling guilty about it. John’s criticism triggered another “feeling guilty” cycle. She has some self-loathing about her life problems.

What’s going on here is that Mary has an internal disagreement she hasn’t resolved. She periodically takes one side of the disagreement (engaging in a lifestyle she has some doubts about or criticisms of). Then she periodically takes the other side in the disagreement (feeling bad about her lifestyle). She’s not rationally investigating the truth of the matter and trying to figure out a solution that will get all the parts of her own mind satisfied and happy. Instead, she’s just alternating which side of herself gets to be in charge. Like many unprincipled compromises, the result is a mess.