Key:

- ✅ for correct,

- ❌ for incorrect answer or missed issue entirely,

- ✅ ❌ for partially correct,

- ⁇ for points I raised that were not addressed in lecture,

- ❗️for stuff I thought was interesting, and

- 😬 for problems that I was low confidence on when I answered them.

I give both an overall mark to each problem and individual marks to subparts.

I had a lot of trouble with ambiguity as to what was intended by the various expressions in this exercise. I managed to keep moving forward anyways. I speculate that it is perhaps challenging to “break” sentences or passages in certain ways without rendering them ambiguous, since a big part of the standard by which we judge an “unbroken” sentence is its clarity.

The instructions for 1 through 9 are:

Identify any errors or deficiencies in diction.

In some cases I do rewrites despite that not being asked for until later problems.

At the very beginning of the homework review, before doing problem 1, Peikoff specifies that the implication is that all of these should be formal English. That’s a pretty important instruction that was not specified in the homework instructions. In some cases I updated my answers to be in formal English.

✅❌ Problem 1

The soloist at Carnegie Hall scampered across the stage and tucked his fiddle under his chin.

✅ “Scamper.” Replace the word “scamper”. I think this is a connotation issue and not a denotation issue per se. The word “scamper” has a connotation/association with children that would typically be odd to bring up in the context of a soloist at Carnegie Hall (unless one were actually describing a child, going for humorous effect, or some other special context.) “walked” or “ran” or “hurried” would be better (depending on the meaning intended).

Peikoff: Bad connotation for a dignified context like Carnegie Hall.

✅ “Tucked”. (Wrote a lot, but at the end of the day I said I would change the tucked)

“tucked his fiddle under his chin” is drawing a lot of attention to a particular act associated with playing the fiddle (the tucking). If that’s the intention and the context is appropriate for that, then that’s okay. The language adds a bit of color. Otherwise, “prepared to play his fiddle” would be a less vivid but more neutral description. Depending on the intent, there is a potential level of abstraction issue here. I’m going to leave it as is, though.

My rewrite:

The soloist at Carnegie Hall [hurried] across the stage and tucked his fiddle under his chin.

Update: With Peikoff’s clarification that he intended formal English, I’d rewrite this, removing the tucked bit:

The soloist at Carnegie Hall [hurried] across the stage and [prepared to play his fiddle].

Peikoff: “Tucked” has a formal usage (as in tucking in a mattress sheet) but that is inapplicable here.

❌ (missed this issue) – fiddle is a colloquial word for violin.

✅ ⁇ ❗️ Problem 2

He was oblivious to the noise, being completely absorbed in the chemical solution which he was preparing. (F&S)

✅ Replace “absorbed in”. Peikoff might classify this as a half-dead metaphor coming back to bite you. The choice of “absorbed” is unfortunate and makes this sentence sound like a description of a Joker origin story. One definition of absorb is “To suck up; to drink in; to imbibe; as a sponge or as the lacteals of the body.” (Webster’s 1913) So it sounds like the guy is possibly submerged in the chemical solution, when presumably the intent is that he’s really focused on preparing the chemical solution.

Peikoff: LP says it’s a metaphor issue.

⁇ (not addressed by LP) “Which he was preparing” could be expressed as “the preparation of” and moved around elsewhere in the sentence:

Rewrite:

He was oblivious to the noise, being completely [focused on] the preparation of the chemical solution.

❗️ (missed this issue but Peikoff says it’s dying off) “oblivious to”. Peikoff says this is a subtle issue and this distinction may be dying out, but the idiom here is “oblivious of”, not “oblivious to”.

✅❌😬 Problem 3

He alluded to the fact in no uncertain terms. The doctors, he said, had never discovered the source of his headache.

❌ (this is an irrelevant issue I brought up due to missing the main issue in the sentence) “Fact”. Which fact is “the fact” referring to? The passage almost wants to read like “He alluded to the fact [that] the doctors [had] never discovered the source of the headache.” It is possible that I am misunderstanding the intent.

✅ Strike “in no uncertain terms” as a trite expression or unnecessary qualifier.

But then we have a problem, which is that the passage becomes:

He alluded to the fact[]. The doctors, he said, had never discovered the source of his headache.

The second sentence brings up the fact that he said stuff, but doesn’t bring up the fact that he said so “in no uncertain terms.” So let’s bring back the essence of idea of alluding to something “in no uncertain terms”, which I take to be that the idea was alluded to forcefully. So, strike the entire first sentence, and then slip an adverb in the former second sentence, which is now the only sentence:

The doctors, he said forcefully, had never discovered the source of his headache.

I still don’t like this sentence. Seems better than what we started with, though. The main story here seems like it should be the failure of the doctors to discover the source of the headache. By cutting the stuff about allusion we make the remaining stuff about the doctors more prominent. Ideally, we’d have a quote, and could just say:

“The doctors have never discovered the source of my headache”, he said forcefully.

But we weren’t given a quote so we’ve gotta do the best with what we have.

❌ (Missed this issue because I had trouble figuring out what was going on in this passage) – Alluded is wrong. An allusion is an indirect/inexplicit reference but the sentence contradicts that by saying the guy said stuff in no uncertain terms.

Analysis: I was very focused on the relationship between the sentences and missed a much easier/simpler issue that Peikoff had in mind. Once I heard Peikoff describe the issue, it became super clear to me what the problem was – so much so that I’m not sure how I missed it.

❌ (Missed this issue) The word “source” in the second sentence is wrong. Should be “cause”.

A cause is that which produces. A source is that from which something came or began.

✅❌ ⁇ 😬 Problem 4

Although he is a cynic certain of nothing, he was very prepared for our meeting and anxious to get a raise; in fact, he was liable to do anything to get it.

✅ (Giving myself credit for this one cuz I identified the issue, even though I waffled some on what to do). Denotation issue re: “cynic.” I think the intent is to say that he’s a skeptic certain of nothing. A cynic is someone who thinks the worst of people – a skeptic is someone who is certain of nothing. So possibly strike “cynic” and replace with “skeptic”. Although I suppose you could say that since cynicism is about thinking the worst of people, maybe the context being implied here is that he doesn’t trust other people not to try to screw him out of a raise. So I’m not sure.

⁇ (was not addressed by Peikoff) Denotation issue. Why “although”? Being certain of nothing doesn’t seem to contradict being prepared for stuff. In fact, if one is certain of nothing, it seems like one might try to be overprepared, since one can’t take anything for granted (impossible to live by this approach IRL but you could try to overprepare for lots of stuff on a selective basis). Also the whole expression is wordy. “Being cynical” (or “Being skeptical” if my last paragraph is right) would be way shorter.

✅❌❗️(I identified that there was an issue with the word “very”, but Peikoff had some reasoning and nuance I was not aware of). Strike the “very”. Pointless intensifier.

Peikoff: In formal usage, “very” cannot be used to modify a participle. You have to say something like “He was very much distressed”, or “he was too-well prepared”. This is an idiom issue, according to LP. I have never heard of this before.

❌ (got the nature of the issue wrong) Possibly strike “;in fact, he was liable to do anything to get it.” because “liable to do anything to get it.” is trite. It also may be wrong. Is the intention actually that the guy under discussion would be willing to e.g. commit murder for a raise?

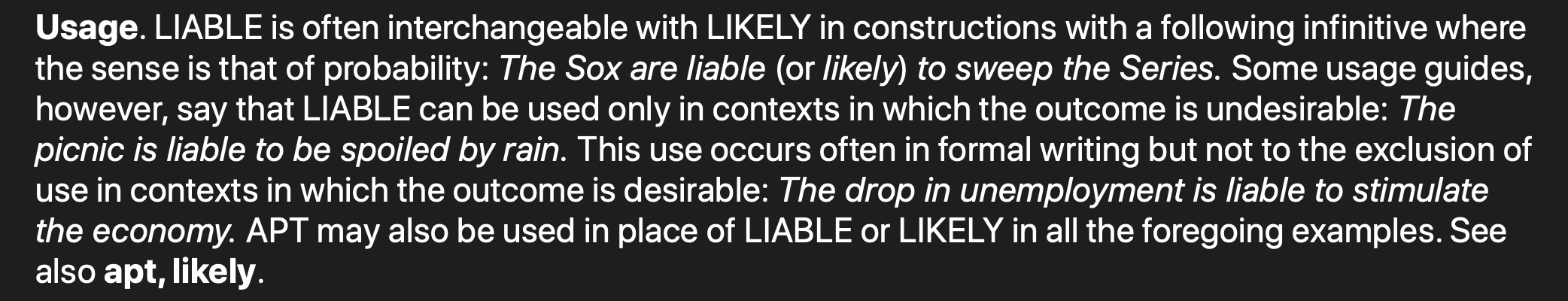

Peikoff: Peikoff says “liable” is the wrong word – means to be held accountable, responsible – and what you want is “likely” to suggest probability. Liable sounded okay to me. Random House Webster’s has the following usage note:

❌(missed issue) “Anxious” is wrong. The word you want here is eager.

Analysis: I agree that would be the better word.

✅ Problem 5

In ancient Egypt, the stature of statues was established by statute.

Euphony violation. Rewrite:

In ancient Egypt, the height of statues was established by law.

✅❌ Problem 6

These activities are employed sooner or later by lots of visitors. Some get a huge kick out of football; the balance are into tennis or golf.

✅❌ Strike “employed” (wrong word) and replace with “enjoyed.”

Peikoff: points out that the best revision would be to talk in terms of games being played.

✅ “get a huge kick out of” is awkward to use to talk about football. Metaphorical usage of kick is clashing with a situation where you actually kick things. Strike and replace with “enjoy” or “play”.

✅”the balance” seems a bit awkward here to juxtapose with “some”. Try “others” or “the rest”.

❌ (missed issue) “lots of” is colloquial for “many”. Remember that this is supposed to be formal English.

✅❌ ⁇ Problem 7

The ship limped into port in the nick of time with its best foot forward. Do you plan on boarding her?

✅”Limped into port” is pretty standard but might be trite for that very reason. I would leave it in anyways and strike the rest of the metaphors.

✅ Strike “in the nick of time with its best foot forward”. Mixed metaphor, vague.

Peikoff refers to “limped into port in the nick of time with its best foot forward” as a “pile of bromides”. He also points out that there is an unfortunate contrast between the “limping” and the “best foot forward”, heh.

⁇ (Peikoff didn’t address the following point about “her” directly — a student brought up that there might be a consistency issue, I think between “her” and “ship”, but the colloquialness was not addressed).

“her” is pretty colloquial re: a ship, so this may be a connotation/formality issue. Maybe “it” would be better depending on the context. Update: given that the context is supposed to be formal English, definitely get rid of “her” and replace with it.

❌ (missed this issue) the idiom is “plan to”, not “plan on”.

✅❌ ⁇ Problem 8

Thanks to pragmatism, the means of education at the disposal of Americans are stunted and sterilized.

⁇(Peikoff didn’t address) “at the disposal” sounds a bit weird in this context. Like I think of servants or lower rank people being at your disposal, not education. Maybe “available” would be better? “means of” is unnecessary.

✅❌ (I noted that it was vague, and Peikoff says it’s overly abstract, so there is some overlap there, but Peikoff brought in an additional point). “stunted and sterilized” seems a bit over the top in terms of metaphor. Also kinda vague. It’s not that long though, could keep it if you want. Two things like that seems like okay alliteration.

Peikoff: “stunted and sterilized” is being applied to “means”. “Means of education” is a very abstract and thus a bad match for a “stunted and sterilized” metaphor, because stunted and sterilized are terms that generally come up in a biological context.

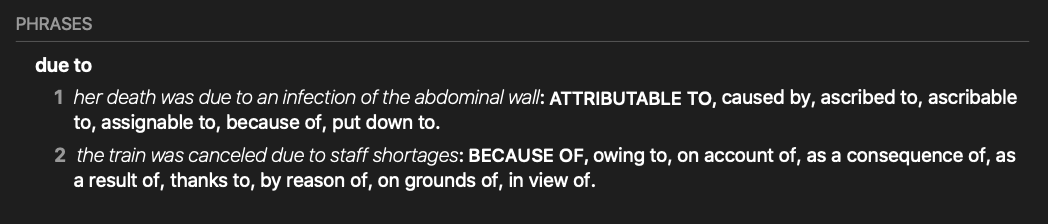

✅ If this was a formal context, “Thanks to” might be too informal. You could do a one-word edit though and change “Thanks” to “Due” without making it stuffy. Hey it’s even shorter 🙂

Shorter than many other equivalent expressions (see definition 2)

Peikoff: Acknowledges that “thanks to” could be a bit colloquial, though he seems to think it’s not a major issue.

Rewrite:

Due to pragmatism, American education is stunted and sterile.

✅ Problem 9

- (a) The resettling of his establishment in New York engendered in him a substantive degree of vituperative affect.

lol. Super excessive wordiness. “Resettling”, “establishment”, “engendered” “substantive”, “degree”, “vituperative”, “affect” (affect indeed! 🙃)

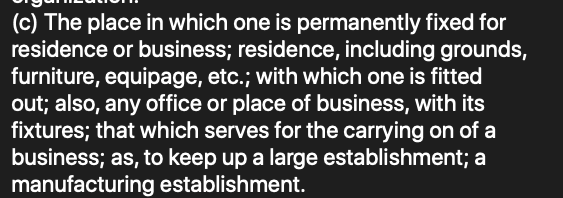

BTW to me, “establishment” connotes a business, but Webster’s 1913 says it could mean either business or residence:

I think one could talk of getting “established” in a new place one moved to, but would generally not talk of an “establishment.” The sentence is pretty ambiguous in terms of whether the context is residence or business.

I don’t want to go through each single overly wordy word carefully to look for the perfect wording, so here’s a rewrite with something like the same content:

Moving his business to New York caused him much anger.

Part 2 of the problem:

(b) He got plenty mad after locating in N.Y.

Very casual/colloquial/slangy, on account of “got”, “plenty”, “mad” and the abbreviation “N.Y.”.

Peikoff: LP passes over this example pretty quickly. I think I got the general idea. An additional point he mentions is that in the wordy version, the actor (he) isn’t the subject.

✅ Problem 10

The instruction for problem 10 is:

Rewrite informal English.

I wonder if there is a typo here, and this was meant to be “Rewrite in formal English”, or if it is saying to rewrite this english that is informal. I’m guessing it is the former, because Peikoff actually used the term “Formal English” in lecture but referred to other stuff as “colloquial English” or “slang” respectively.

The statement:

He could’ve been cool if he’d had it more together.

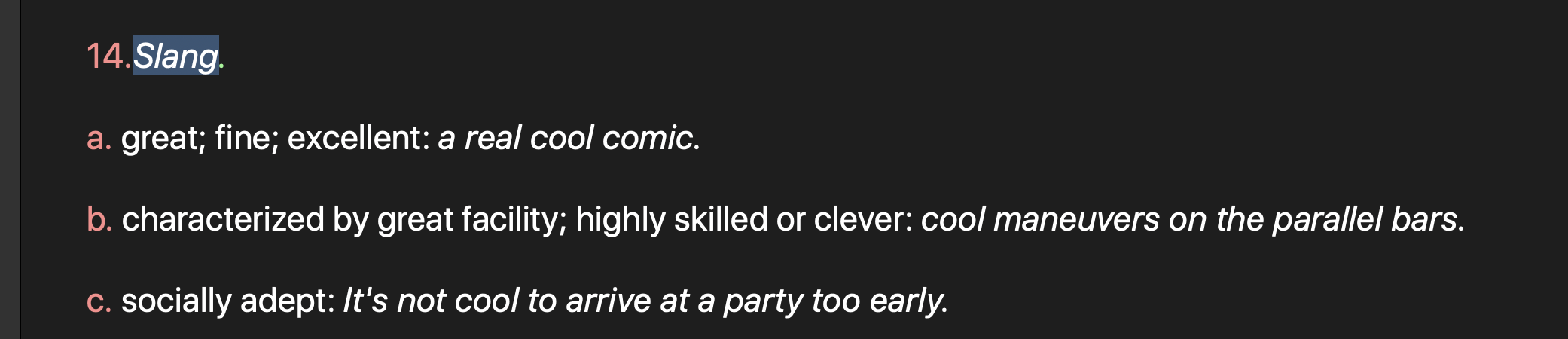

Random House Webster’s gives the following definitions for “cool” as slang:

And for “together” the same dictionary says:

m-w.com gives the following for “get it together”, which seems related:

IMHO the original statement is unclear. I can try to interpret it as best as I can though.

“He could have been a fine individual if he were more well-adjusted.”

Seems okay.

Peikoff: The point of this was to show how vague it was and how many different ways it could be interpreted. Mission accomplished!

✅❌😬 Problem 11

Distinguish among the following:

first word:

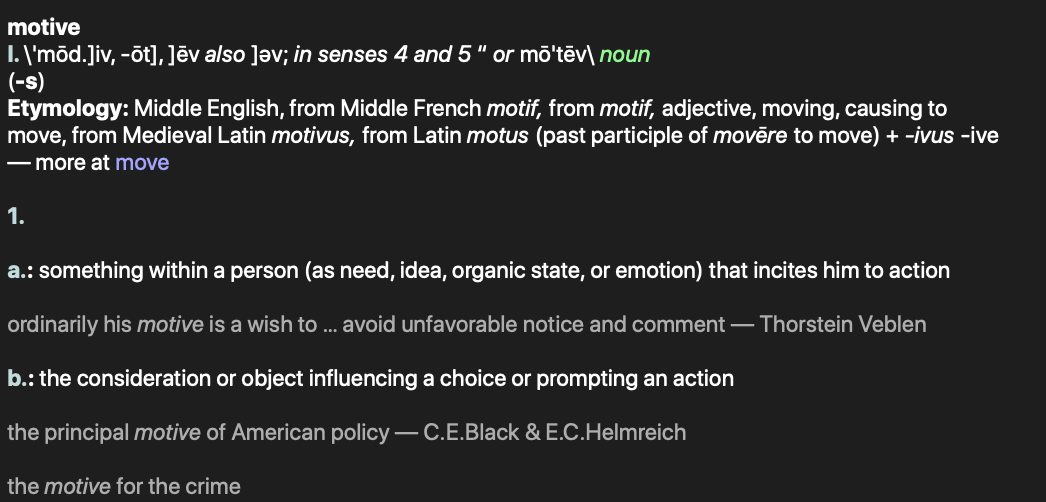

motive

✅❌ (got some of the idea of internal motivation that Peikoff describes, but didn’t state the issue with full clarity)

Webster’s Third:

So a motive is about why someone is doing something.

A motive could be things like: curiosity, interest, love, passion, vengeance, an ideological motivation, a desire for food or shelter, etc.

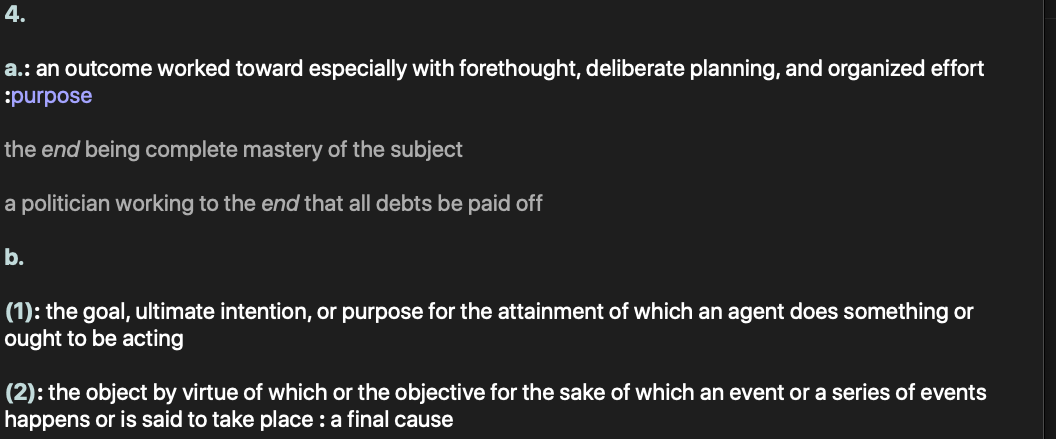

end

✅

Webster’s Third:

So an end is kind of like a long-range goal that you put lots of effort or planning into.

purpose

❌ (purpose has some longer range connotation, contrary to what I say, below, but end has an even longer range connotation. I seem to have actually grasped this in my examples but I misstate the issue here)

Webster’s Third:

So a purpose seems similar to an end but lacks the longer-range connotations of that, maybe?

goal

✅

For goal, Webster’s third gives the following definitions:

So a goal seems like something more concrete and specific that you’re aiming to get (especially in light of the connection to a racing mark).

So you might have a savings goal of $500 a month, or a goal of writing 1000 words a day. Goals seem like they would often be tied to numbers (not necessarily, but it makes more sense to talk about a “savings goal” than a “savings end”.)

That said, you could talk about bigger picture things in terms of goals (changing the world), but I’m trying to tease out the differences in the words here.

Some concrete examples where I try to contrast end/goals/purpose/motive.

Guy with a family saving for a Disney Trip:

1. Motive: A desire for leisure, enjoyment, making family happy.

2. End: Having an overall happy family life/happy life.

3. Purpose: Having the resources to take a trip this coming summer.

4. Goal: Having X dollars saved by June.

Founding Fathers fighting the British:

1. Motive: desire for liberty & freedom from oppression

2. End: the establishment of a long-lasting system of free government for themselves and their posterity.

3. Purpose: establish, in the near-term, a government that respects individual rights.

4. Goal: defeat the British military.

Rand talks about motive, purpose, ends and goals here:

The motive and purpose of my writing is the projection of an ideal man. The portrayal of moral ideal, as my ultimate literary goal, as an end in itself to which any didactic, intellectual or philosophical values contained in a novel are only the means.

Peikoff:

According to most dictionaries, motive is about inner state that prompts you to act, and the other three — end, goal, and purpose — refer to outer things you want to accomplish.

Purpose implies a long range course of action. End is even longer range.

For example:

The purpose of law is to resolve disputes. The end of law is liberty.

Goal has less agreement re: what it means. But goal is broader and include unconscious entities. Also goals are more specific and concrete.

✅❌ Problem 12

Rewrite, making the adjectives more specific.

The girl looked nice (though her boyfriend was big), and the movie was no good. So Bill decided to speak to her. It was a bad mistake.

IMHO there is an ambiguity re: “big” in light of “though.” Is “big” establishing a contrast with “nice”? Like, is there something bad about the “big”? E.g. is the boyfriend fat? Or on the other hand, are we being told that the boyfriend is big as in muscular or something like that because that helps establish some context as to why Bill deciding to speak to the girl was a bad mistake?

Bill saw an alluring girl while watching a movie. The movie was poor, so Bill decided to speak to the girl despite the presence of her muscular boyfriend. This decision was a terrible mistake.

Peikoff thinks that words like “terrible” are trite. I’m not sure.

Looking back, I think “the movie was poor” isn’t great idiomatically. “The film was poor” or “The movie was boring” would be better.